Talking Taijiquan with David Gaffney

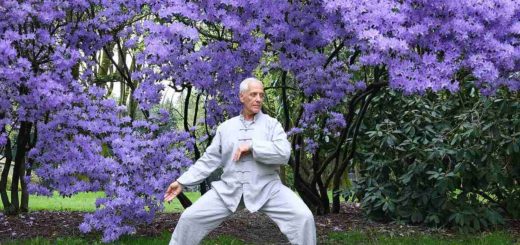

Life is always richer and brighter when you happen to meet knowledgeable people who are friendly, modest and helpful at the same time. David Gaffney is all of that. He has practised Asian martial arts since 1980. His Chen Taijiquan training began seriously in 1996 when he met Chen Xiaowang, later doing a formal discipleship ceremony with him. In 2003 he was formally introduced to his brother Chen Xiaoxing in Chenjiagou in order to receive more personalised training and has carried on training with him to this day.

David is also a co-founder of Chenjiagou Taijiquan GB and co-author of 3 books about Taijiquan: Chen Style Taijiquan: The Source of Taiji Boxing, The Essence of Taijiquan and the newest one which has just been published – Chen Taijiquan: Masters and Methods.

David, have you always been interested in martial arts? What made you “switch over” to Taijiquan?

Yes! I began training martial arts with a school friend who told me about a Karate club he had heard of. I can say it was love at first sight and from the first day I stepped into the training hall I was hooked. For the next fifteen years I trained external martial arts. Later I heard about a Chinese teacher teaching Chen Taijiquan in Manchester and began learning Taijiquan – first simply as an interesting area of cross training to supplement what I was already doing. I switched completely over to Taijiquan when Chen Xiaowang came to Manchester to do a seminar in 1996. After a short lecture on Chen Taijiquan Chen Xiaowang stood up and demonstrated the system’s fajin. At the time he would have been about fifty years old and his explosiveness was on a different level to anything I’d seen before.

How long have you been practicing Taijiquan? Has your attitude changed over the time?

As I said in the previous answer, I began practicing Taijiquan in the mid 1990s. Like most people who move across from the external systems, in the beginning I tried to understand Taijiquan in relation to my previous training. In time, though, I came to realise that Taijiquan has its own distinctive methodology. Like any other Chinese martial art, training is centred on developing the four key areas of shou yan shenfa bu (hands, eyes, body and footwork), at the same time working to enhance speed and strength.

Taijiquan, however, approaches this through, at first sight, the contradictory methods of slowness and softness. Speed is increased by working to rid the body of all traces of stiff energy and training the body to work as an integrated system where every action is natural and unforced.

Taijiquan, however, approaches this through, at first sight, the contradictory methods of slowness and softness. Speed is increased by working to rid the body of all traces of stiff energy and training the body to work as an integrated system where every action is natural and unforced.

Slow training is used to increase synchronisation throughout the body parts involved in any particular movement. This brings many practical benefits, for example when releasing power a skilled practitioner can focus the power of the whole body onto a single point and can fulfil the requirement of generating power from the feet, directing it with the waist and releasing it through whichever part of the body is being used to strike an opponent.

As to my own training, my emphasis has naturally changed and developed over time. During my years doing external martial arts I enjoyed competing and in the early years of Taijiquan training I was interested in this area. Chen Taijiquan has a wide curriculum and in the beginning there always seemed to be something interesting and new to learn. However, this is not really the essence and as the years have gone by I’ve come to realise the fact that Taijiquan training is a difficult and on-going process. For instance, it’s very easy to quote the rules of the system, but how many people actually fulfil them.

Regardless of whether people are doing forms or push hands, without maintaining the correct body structure, energetic quality and intention you can’t really call it Taijiquan.

Today I appreciate the need to use mindful training to embed the many different requirements and, in practice, keep going back to these fundamentals. At the end of the day Taijiquan movement follows a body philosophy that supports naturalness, spontaneity and balance. There is no room for excess of any kind. Externally the left and right sides, upper and lower body and forward and backward aspects harmonise with no contradiction or friction. Internally there must simultaneously be a sense of calmness and of awareness. To try to approach this level of mental and physical balance requires the acceptance of daily training as a type of ongoing self-cultivation.

Who is your teacher and why do you study with him? Where else do you get inspiration for your training?

I’ve trained martial arts for almost four decades now with a number of excellent teachers whose influence continues to resonate with me. In terms of Taijiquan, I was fortunate to be introduced to Chen Xiaowang and Chen Zhenglei early in my Taijiquan training and over the years I’ve tried to get as much experience as possible training with high level teachers including Zhu Tiancai, Wang Xian and younger teachers such as Chen Ziqiang and Wang Haijun.

I’ve trained martial arts for almost four decades now with a number of excellent teachers whose influence continues to resonate with me. In terms of Taijiquan, I was fortunate to be introduced to Chen Xiaowang and Chen Zhenglei early in my Taijiquan training and over the years I’ve tried to get as much experience as possible training with high level teachers including Zhu Tiancai, Wang Xian and younger teachers such as Chen Ziqiang and Wang Haijun.

I’ve trained with Chen Xiaoxing since 2003 and consider him to be my primary teacher. I find his no nonsense and no frills approach and emphasis upon fundamentals to be a good fit. His teaching method is very much built around doing rather than talking and of developing self reliance and an acceptance of repetition training and the fact that there are no short cuts.

What comes to mind first when someone says: “Taiji“? People today mention health effect, meditation, relaxation… Has the purpose of Taijiquan changed as people´s lifestyle changes?

Rather than saying the purpose has changed, I would say that more and more people come to Taijiquan with incorrect perceptions about its real nature. So much of the media portray Taijiquan as a kind of soft and easy option that requires little in the way of commitment from participants, an exotic kind of slow motion “spiritual” exercise. As a result many people arrive at their first class with no idea it is a martial art and, in truth, with no interest in martial arts.

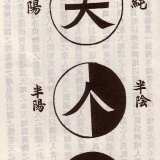

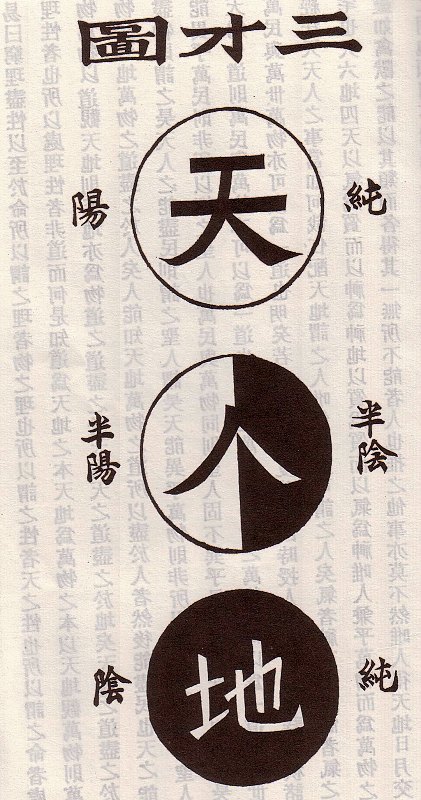

Most people refer to the system as “Taiji” or more commonly “Tai Chi”, and are not aware that its correct name is Taijiquan. The name consists of two components: “Taiji” is a philosophy drawn from the Yijing (Book of Change) – a philosophy that seeks to find and maintain a state of optimum balance. “Quan” refers to a form of martial art. Together the name Taijiquan denotes a martial art based on a particular type of philosophy.

Most people refer to the system as “Taiji” or more commonly “Tai Chi”, and are not aware that its correct name is Taijiquan. The name consists of two components: “Taiji” is a philosophy drawn from the Yijing (Book of Change) – a philosophy that seeks to find and maintain a state of optimum balance. “Quan” refers to a form of martial art. Together the name Taijiquan denotes a martial art based on a particular type of philosophy.

The original purpose of Taijiquan was martial arts. Health enhancement, mental calmness and a relaxed and integrated body are the secondary benefits of training Taijiquan. All of these positive states are the by-products of training the traditional system.

Can people get some of the benefits you mentioned like “health effect, meditation, relaxation” without being aware of the martial aspect of the system? Probably. For example, if someone only trains the standing pole and form, paying attention to mental calmness and developing a better physical structure should in time benefit health and relaxation.

Does that mean they are training Taijiquan? I would say no. It’s like comparing the training in a traditional western boxing gym with a “boxercise” class in a health club. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with either of them, but they are just not the same thing. The people who do boxercise might be physically fit, but they will not be able to compete in a ring.

Chen Taijiquan is an ancient martial art and to lose sight of this is to lose sight of its very essence.

The breadth of the curriculum points to the level of thought that has gone into developing the art: forms, weapons, push hands from single hand drills all the way up to sanshou etc., single movement and partner work, and supplementary training such as standing pole, reeling silk exercises and equipment such as the long pole and taiji bang etc. The art wasn’t created from a vacuum, but drew from many different sources including China’s extant martial arts, yin-yang theory from the Yijing, traditional health practices such as daoyin tu-na (leading and guiding energy and breathing methods) and elements from Traditional Chinese Medicine including the jingluo (channel and meridian) theory.

That said, everyone’s capabilities are different in terms of age, fitness, natural ability etc. Today the average beginners that come through our doors are middle aged (or older) and often in quite poor state of health and fitness. The most basic requirement for any martial art, including Taijiquan, is a decent level of fitness. I remember meeting the late grandmaster Feng Zhiqiang in Beijing. He made the point very clearly that

robust good health is the foundation that must be in place before anyone could begin to think about martial arts in any meaningful way.

Naturally a person’s emphasis will change over time. It is quite normal for a young person to be drawn to the explosive and athletic side of the system and for an older person to realise the importance of preserving health and mobility. But beyond this one of the great things about Taijiquan is the way through which different personalities can find expression: the exploration of the systems combat potential; using it as a means of aesthetic expression or as a doorway to understanding a very different culture and philosophy.

What is the most effective way to train and study Taijiquan?

To begin with, no two people are the same and progress depends on a person’s natural abilities. The best results should be approached with the idea of learning for yourself, not in competition or comparison with other people.

To begin with, no two people are the same and progress depends on a person’s natural abilities. The best results should be approached with the idea of learning for yourself, not in competition or comparison with other people.

Assuming you have found a knowledgeable teacher, the first requirement is hard work. Most people have heard the expression “eating bitterness”. However, training hard on its own is not enough and must be accompanied by a correct understanding of Taijiquan’s principles and philosophy. My teacher Chen Xiaoxing often repeats the phrase “you know the rules, follow the rules”! Taijiquan has many requirements both in terms of each part of the body and how it relates to the whole and the system’s method of moving sequentially joint-by-joint. Training is approached systematically, step-by-step and skills built up layer by layer.

A common saying

“Taijiquan is easy to learn and difficult to correct”

points to the fact that it is harder to undo ingrained mistakes than to learn properly in the first place. Learning properly requires patience and the willingness to train certain attributes, before progressing up the skills ladder. A simple example would be the practitioner who is in a hurry to train applications without first laying down fundamental foundation i.e. a solid and rooted lower body and supple and loose upper body. This will severely limit the ultimate level of ability. Progressing from one stage to the next is dependent upon acquiring the appropriate degree of technical skill at each level.

One of the Chen style masters mentioned that without the Daoism philosophy context and understanding you are not able to understand and get to the true meaning of Taijiquan? Do you agree with that? Why yes or no?

Yes, I would agree with that statement. Taiji (philosophy) has been a core component of Chinese culture for thousands of years and many elements essential for good Taijiquan practice, such as not over thinking, moving in a natural and harmonious way, are embedded within Chinese culture. Ideas such as wuji, wu-wei, yin-yang, ziran etc. are rooted within Daoist philosophy and are fundamental if one is to get beyond a superficial understanding of Taijiquan. In fact, these ideas and concepts are ever present throughout Chinese life whether it be literature, warfare, medicine, philosophy etc.

Many of the ideas of Taijiquan can be traced back to China’s famous military strategist and Daoist philosopher Sunzi.

He spoke of the use of shi, or potential energy, illustrating this with the idea of a large rock perched above a chasm. The potential force of the rock is not revealed, but held ready in reserve; that with a small push will be unleashed on a unsuspecting enemy below. This is similar to Taijiquan’s concept of maintaining strength “in eight directions”, where the body and mind are in a completely balanced state ready to react to an attack from any direction instantaneously and without any telegraphing of one’s intention.

Western thinking often seeks to understand by breaking things down into their component parts. During practice you often hear questions such as “Is my hand in the right position?” or “Are my hips correct?” Daoist thinking, on the other hand, is quite clear on the idea that things can only be understood in relation to the whole and that nothing can be understood in isolation.

Western thinking often seeks to understand by breaking things down into their component parts. During practice you often hear questions such as “Is my hand in the right position?” or “Are my hips correct?” Daoist thinking, on the other hand, is quite clear on the idea that things can only be understood in relation to the whole and that nothing can be understood in isolation.

We can see examples of these relationships in Taijiquan theories, the most simple of which are the guidelines for the requirements of the body in Chinese: “relax the shoulders and sink the elbows”, “relax the kua and round the crotch”, “sit the wrists and extend the fingers”, “look forward and listen behind” etc. Every requirement is in relationship to another, which is not often emphasised in the West.

The understanding that we are working on the body and mind as a unified system is essential if we are to get beyond a shallow understanding of Taijiquan.

Do you think that non-Chinese people can learn Taijiquan as well as Chinese? Zhu Tiancai’s youngest son Zhu Xianghua said, that it is something like playing football – the Europeans and others have it in their blood. So do Chinese people have Taijiquan in their blood?

I don’t really like limiting beliefs like this. Obviously Chinese students have certain cultural advantages and many of the terms and frames of reference used in Taijiquan are familiar and everyday to them. Western students do face real barriers in terms of language and culture and I think that to progress it is necessary to embrace and try to understand that culture.

To take the football analogy of Zhu Tiancai’s son I would say that if we take the English Premier League as an example, for sure the majority of players are European or South American – countries that can be said to “have football in their blood”. However, Chinese players like Sun Jihai at Manchester City and Zhang Yuning at West Bromwich have shown that it can be done.

To take the football analogy of Zhu Tiancai’s son I would say that if we take the English Premier League as an example, for sure the majority of players are European or South American – countries that can be said to “have football in their blood”. However, Chinese players like Sun Jihai at Manchester City and Zhang Yuning at West Bromwich have shown that it can be done.

I remember when we interviewed Chen Bing in Chenjiagou back in 2003 and put a similar question to him. He suggested that the main advantage he had over other people (read westerners) was the constant access to high level coaches from an early age and a ready supply of good quality training partners. You could say the same thing about the Chinese football players.

As a point of interest, I saw an interview recently in which one of the instructors of the Chenjiagou Taijiquan School, still only in his late twenties himself, said that the younger generation of students – for the most part – were more interested in playing with their mobile phones than in training and did not train as hard as before. At the end of the day you have to do your best, train hard and don’t think in a negative way.

Why would you recommend Taijiquan to people? (It is said to be a way of life, it affects the whole personality…)

Taijiquan is a system that makes considerable physical demands of practitioners, but at the same time calls for total mindfulness in terms of every aspect of movement and position. Assuming an individual is following the correct method, they can expect to become calmer, stronger and more co-ordinated and balanced over time. Whether one is interested in combat, aesthetics, fitness, Chinese culture and philosophy etc., all practitioners must conform to the same rules and principles. Approached this way Taijiquan is a system that can provide a focus of study and personal growth over the course of a lifetime.

What Taijiquan skills (ability, attitude…) do you use in practical Taijiquan. What does practical Taijiquan mean for you?

Practical to me means not training in an “empty” way. For example, when training the form, striving to use intention rather than mindlessly grinding out repetitions. Intention focused upon either training distinct capabilities such as rootedness, correct movement route (for instance using the body’s centreline as an exact boundary), awareness etc., or upon understanding the potential functions of each movement.

Practical to me means not training in an “empty” way. For example, when training the form, striving to use intention rather than mindlessly grinding out repetitions. Intention focused upon either training distinct capabilities such as rootedness, correct movement route (for instance using the body’s centreline as an exact boundary), awareness etc., or upon understanding the potential functions of each movement.

At the same time it is important to constantly work to cultivate the correct mental state. It doesn’t matter how strong or beautiful a person’s techniques are, or how many applications they know if they crumble under pressure. Training in Beijing some years ago with Tian Jingmiao, a disciple of Lei Muni (himself a senior student of Chen Fake), she recalled the way her teacher always carried a copy of Sunzi’s Art of War – constantly reflecting on it and how to apply it to his Taijiquan.

Sunzi is infused with ideas such as: developing your own power and confidence without feeling the need to overtly display it; or the need to maintain calmness to be able to deal effectively with chaos and confusion. Developing this kind of balanced and clear mental state is equally relevant whether we’re talking about combat or about the stresses of everyday living.

Practical also means training in a flexible and intelligent way to be able to keep progressing. In your teens or twenties it can feel as if you are indestructible, injuries heal quickly and you recover from hard training almost instantly. I’m in my mid fifties now and very aware that the human body needs to be nurtured if it is to last the course. With this in mind I spend a fair amount of time every day going through a routine of injury prevention and core training exercises.

What aspect of your Taijiquan would you like to improve?

All of the qualities I mentioned in the previous answer.

You have written 3 books about Taijiquan? What motivation did you have? Did writing books help you with your Taijiquan understanding?

Yes, I’ve co-written three books about Chen Taijiquan with my wife Davidine Sim. At first the motivation was to get some accurate content out in English. As we touched upon previously, Taijiquan is an incredibly misrepresented and misunderstood art. There’s no doubt that the research process of the books helped me to get a better understanding of what Taijiquan is. We’ve always looked to present clear content in a non dogmatic way.

Yes, I’ve co-written three books about Chen Taijiquan with my wife Davidine Sim. At first the motivation was to get some accurate content out in English. As we touched upon previously, Taijiquan is an incredibly misrepresented and misunderstood art. There’s no doubt that the research process of the books helped me to get a better understanding of what Taijiquan is. We’ve always looked to present clear content in a non dogmatic way.

We published our third book Chen Taijiquan: Masters and Methods in August this year. With the rapid pace of change, both in terms of Taijiquan and society in general, we wanted to capture the thoughts of the older generation of teachers – teachers who committed to their practice at a time prior to the commercialisation and widespread dissemination of Taijiquan. The book addresses many of the misconceptions that surround Chen Taijiquan presenting the thoughts of a number of high level practitioners.

David, thank you for talking to us… enjoy the time with Taijiquan 🙂

Alena Koutecká

Foto: David Gaffney